TypeScript is a fantastic tool for building scalable JavaScript. When it comes to huge JavaScript projects on the web, it's more or less the de facto norm. As good as it is, there are a few tough sections for the uninitiated. Discriminated unions in TypeScript are an example of this.

Given this code, in particular:

interface Cat {

weight: number;

whiskers: number;

}

interface Dog {

weight: number;

friendly: boolean;

}

let animal: Dog | Cat;

...many developers are shocked (and sometimes outraged) to see that when they use animals., only the weight property, not whiskers or friendly, is valid. This will all make sense towards the end of this article.

Let's take a quick (and required) look at structural typing and how it differs from nominal type before we get started. This will beautifully set the stage for our examination of TypeScript's discriminated unions.

Structural typing

Comparing structural typing to what it isn't is the most effective way to introduce it. The majority of typed languages you've used are ostensibly typed. Consider the following C# code (which would be comparable in Java or C++):

class Foo {

public int x;

}

class Blah {

public int x;

}

Despite the fact that Foo and Blah are identical in structure, they cannot be assigned to each other. The code is as follows:

Blah b = new Foo();

…generates this error:

Cannot implicitly convert type 'Foo' to 'Blah'

It makes no difference how these classes are organized. Only instances of the Foo class can be assigned to a variable of type Foo (or subclasses thereof).

TypeScript works in the reverse direction. If two types have the same structure, TypeScript considers them to be compatible—hence the name structural typing. Is that clear?

As a result, the following code is error-free:

class Foo {

x: number = 0;

}

class Blah {

x: number = 0;

}

let f: Foo = new Blah();

let b: Blah = new Foo();

Types as sets of matching values

Given this code:

class Foo {

x: number = 0;

}

let f: Foo;

f is a variable that holds any object that matches the structure of Foo class instances, in this case, an x property that represents a number. That means that even a simple JavaScript object will work.

let f: Foo;

f = {

x: 0

}

Unions

Thank you for sticking with me up to this point. Let's go back to the beginning of the code:

interface Cat {

weight: number;

whiskers: number;

}

interface Dog {

weight: number;

friendly: boolean;

}

We know that this:

let animal: Dog;

...turns any object into an animal with the same structure as the Dog interface. So, what exactly does the following imply?

let animal: Dog | Cat;

Any object that matches the Dog interface, or any object that matches the Cat interface, is considered an animal.

So why does animal—as it stands now—only enable us to access the weight property? Simply put, it's because TypeScript has no idea what type it is. TypeScript understands that the animal must be a Dog or a Cat, although it might be either (or both at the same time, but let's keep it simple). If we were allowed to access the friendly property, we'd almost certainly get runtime issues, but the instance ended up being a Cat rather than a Dog. If the item turned out to be a Dog, the whiskers attribute would be the same.

Instead of unions of properties, type unions are unions of valid values. Developers frequently write something similar to this.

let animal: Dog | Cat;

...and don't be surprised if the animal has a combination of Dog and Cat traits. But, once again, this is a blunder. This indicates that the animal has a value that is equal to the sum of valid Dog and Cat values. However, TypeScript will only let you access properties that it is aware of. For the time being, this means properties on all of the union's types.

Narrowing

Right now, we have this:

let animal: Dog | Cat;

How do we properly treat an animal as a Dog and access properties on the Dog interface when it's a Dog, and similarly when it's a Cat? We can utilize the in operator for now. This is an older JavaScript operator that you probably don't see very often, but it basically allows us to check if a property exists in an object. As an example:

let o = { a: 12 };

"a" in o; // true

"x" in o; // false

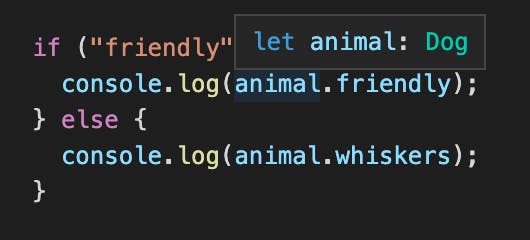

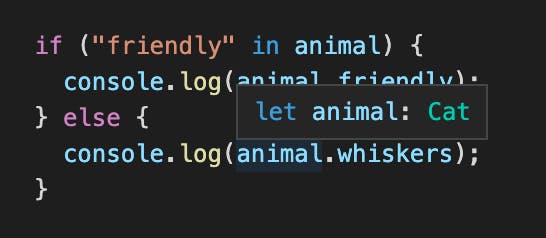

It turns out TypeScript is deeply integrated with the in operator. Let’s see how:

let animal: Dog | Cat = {} as any;

if ("friendly" in animal) {

console.log(animal.friendly);

} else {

console.log(animal.whiskers);

}

There are no errors in this code. When TypeScript is inside the if block, it recognizes the friendly property and casts the animal as a Dog. And TypeScript treats an animal like a Cat while it's inside the else block. You may see this in your code editor if you hover over the animal object inside these blocks:

Discriminated unions

You may expect the blog post to finish here, but checking for the existence of attributes is quite limiting when restricting type unions. It worked fine for our simple Dog and Cat kinds, but as we have additional types, as well as more overlap between those types, things can quickly get more difficult and brittle.

Discriminated unions can help in this situation. Everything will remain the same as before, except that each type will have a property whose sole purpose is to distinguish (or "discriminate") between the types:

interface Cat {

weight: number;

whiskers: number;

ANIMAL_TYPE: "CAT";

}

interface Dog {

weight: number;

friendly: boolean;

ANIMAL_TYPE: "DOG";

}

let animal: Dog | Cat = {} as any;

if (animal.ANIMAL_TYPE === "DOG") {

console.log(animal.friendly);

} else {

console.log(animal.whiskers);

}

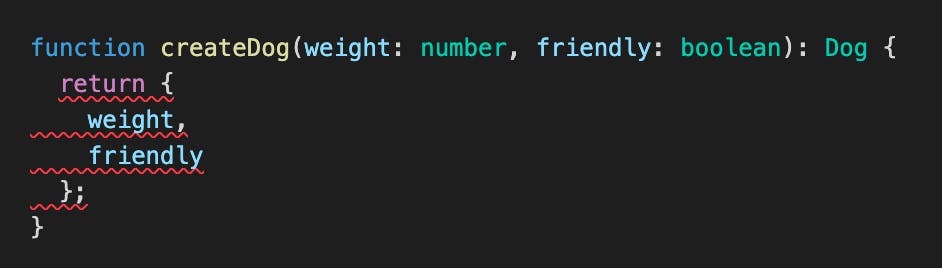

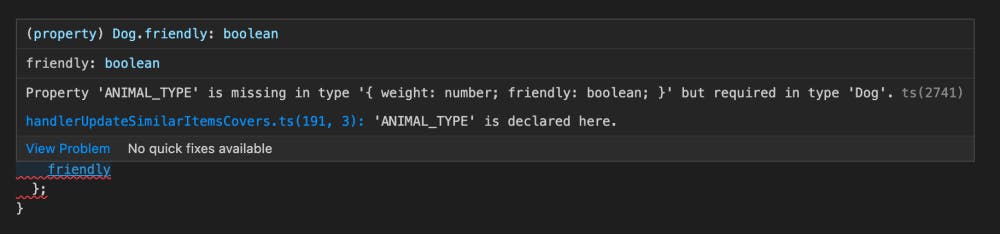

This check becomes flawless if each type participating in the union has a unique value for the ANIMAL TYPE attribute.

The only drawback is that you now have to deal with a new property. You must specify the single right value for the ANIMAL TYPE whenever you create an instance of a Dog or a Cat. However, don't worry if you forget since TypeScript will remind you.

More Insights

I recommend reading the TypeScript docs on narrowing if you want to learn more. That will provide us with a more in-depth look at what we've discussed so far. A section on type predicates can be found inside that link. These allow you to create your own custom checks to narrow types without having to rely on type discriminators or the in keyword.

Conclusion

I stated in the beginning of this article that in the following example, weight is the sole available property:

interface Cat {

weight: number;

whiskers: number;

}

interface Dog {

weight: number;

friendly: boolean;

}

let animal: Dog | Cat;

What we discovered is that TypeScript only recognizes the animal as a Dog or a Cat, but not both. As a result, the only trait that the two have in common is weight.

TypeScript differentiates between those things via discriminated unions, and it does so in a way that scales exceedingly effectively, even with bigger groups of objects. As a result, on both kinds, we had to construct a new ANIMAL TYPE property that carries a single literal value that we can check against. Sure, it's another thing to keep track of, but it also yields more consistent results—which is exactly what we wanted from TypeScript, to begin with.